Why Was Six Afraid of Seven Continuations

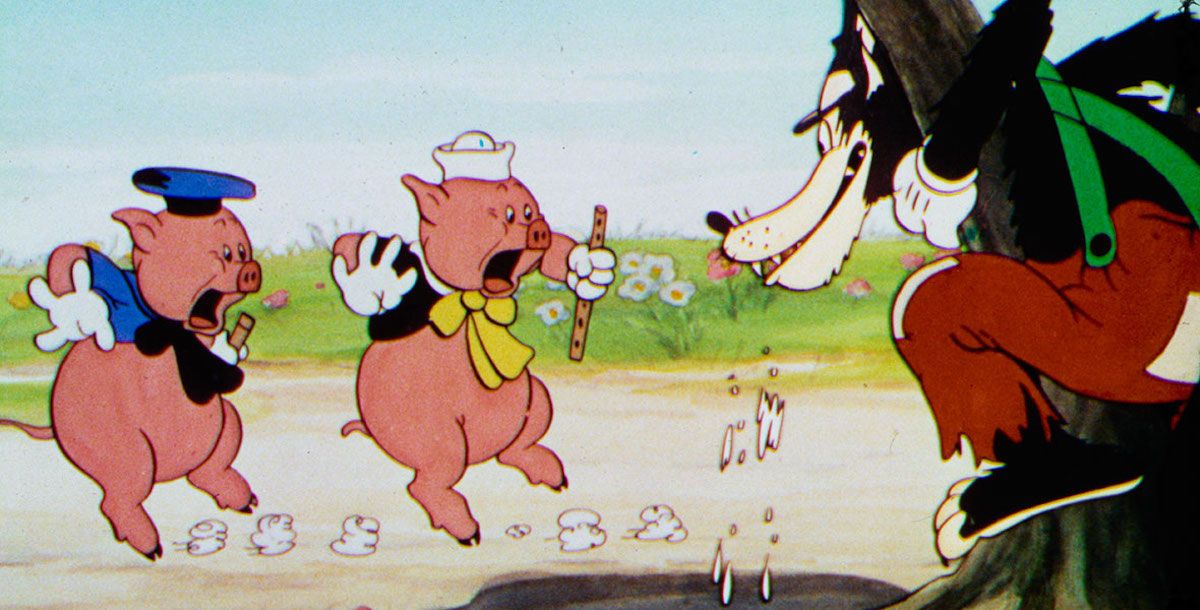

I wonder how aware the kids these days are of the Three Little Pigs. Not the fairy tale itself, the Disney pigs. My generation at least knew of them through singalong VHS tapes and the odd appearance on the Disney Channel, but they've never been mainstays of Mickey's gang. Yet in 1933, "Three Little Pigs" was Walt Disney's first runaway hit since Mickey Mouse. Its song "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?" became an anthem for the Great Depression, while business was so good that the short ran for months in theaters across America.

Then as now, success inspired some parties to look into sequels and series. These parties prevailed on Walt to deliver more pigs. But that wasn't Walt's natural instinct – nor was it as dominant a practice in Hollywood then compared to our times.

"The Three Little Pigs" was one of the Silly Symphonies , the companion series to the Mickey Mouse shorts. By design, the Symphonies did not have a star or any recurring characters. This was partly a business consideration; having lost Oswald the Lucky Rabbit to his distributor, Walt didn't want to depend on a single character. But there were artistic considerations behind this set-up as well. The Symphonies were originally intended to showcase marriages of music and animation in a way that highlighted the soundtrack, and gradually became a laboratory for training new talent and for trying new techniques in animation production and different tones and styes of narrative.

It's very hard now, even for animation buffs, to recognize just what made "Three Little Pigs" so unique when it first premiered. Its innovations are so fundamental and were adopted so widely that they're easy to take for granted. The major breakthrough made in "Three Little Pigs" was in taking three characters who looked alike and distinguishing their personalities by their posture and movement. What's more, the characteristics setting the pigs apart from one another were maintained throughout the short. Animator Fred Moore, a young hire who rose up the ranks quickly, pulled off the feat. Even Walt, notoriously stingy with praise, was impressed. "At last we have achieved true personality in a whole picture!" he wrote to his brother Roy Disney.

That breakthrough, paired with a catchy tune that captured something of the Depression-era zeitgeist, went a long way to making "The Three Little Pigs" a financial success as well as a creative one. According to Walt's biographer Bob Thomas, some theaters billed the short over the feature films it was playing with, unheard of for a cartoon at that time. The success (and the demand for sheet music for the song) caught Disney and their distributor United Artists completely off-guard. With the money and praise flowing in, United Artists implored Walt to provide more pigs.

Always creatively restless, Walt didn't like to repeat himself. A series starring his alter-ego Mickey was one thing; Mickey and pals always got up to new adventures. But a direct sequel in a series that wasn't meant to have any recurring characters held no interest for Walt. His instinct was to take the lessons learned from "The Three Little Pigs" and carry them forward into new productions. Thomas puts brother Roy down as the one who persuaded him otherwise. Walt Disney Productions was only a small cartoon studio in those days, often sailing financially choppy waters. More pigs would be good for business, which would be good for any new characters or stories Walt and his artists cooked up.

United Artists got their wish. Disney provided them with not one sequel, but three: "The Big Bad Wolf" in 1934, "The Three Little Wolves" in 1936, and "The Practical Pig" in 1939 (a fourth film, "The Thrifty Pig," was cobbled together from stock footage for the National Film Board of Canada during World War II). Except for "The Practical Pig," all the original shorts are available on Disney+. They're all cute, charming cartoons. They introduce the Big Bad Wolf's three rotten children, surprisingly and delightfully vicious little devils. The backgrounds and effects animation in all three sequels is more elaborate than in "Three Little Pigs."

The same could be said for a lot of Symphony cartoons, though. And the mini-wolves can't hide the fact that each of the sequels plays out the exact same conflict as "Three Little Pigs." Watching them all in a row, it's not at all hard to see that the pigs and the wolf are one-note characters. They don't have enough range and substance to them to support a sequel, let alone a series like Mickey Mouse, and their tangles with each other can't offer the variety of, say, Wile E. Coyote's schemes to catch the Road Runner at Warner Bros. If anything, repeated adventures make Fifer and Fiddler Pig hard to sympathize with when they keep making the same mistake again and again.

I don't know whether 1930s audiences felt the same way; with these shorts coming out several years apart and almost never screened together, I suspect not. At least one of them picked up polite reviews. But if viewers were content with more pigs, they weren't electrified by them either. None of the sequels replicated the success of "Three Little Pigs," and none of them satisfied Walt either. With this pressured sequel experience generating no great creative or business triumph, Walt adopted a saying he used throughout his career to sum up his instinct on entertainment: "you can't top pigs with pigs!" It's a phrase the modern Disney company has been happy to include in official or sanctioned biographies and documentaries, even as they devote ever more resources into ignoring it.

It's fair to acknowledge that Walt didn't always hold to that philosophy himself. A very few more Symphonies would get sequels. The Absent-Minded Professor , another runaway hit from 1961, got a sequel to use up a few loose gag ideas, though how much interest and involvement had by that point is open to question. But for the most part, Walt's answer to success was to follow it up with something new. It was a pattern he showed even before "Three Little Pigs" in following Mickey with the Symphonies. When Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs became a blockbuster before blockbusters, Walt resisted cries for a sequel and opted for three ambitious films of different visual and narrative character. Even when they all contributed to a drastic reversal in fortunes for the studio, Walt persisted in diversifying into live action. When proficiency in movies caused them to lose some luster for him, he moved into television and theme parks. And of course, the most natural thing in the world after Disneyland was such a phenomenon was to go into universities and experimental cities.

I don't know any other film producers whose ambitions soared quite that high. But Walt Disney was hardly alone in preferring follow-ups to successful films. After Dracula proved him right about the box office potential for horror, Carl Laemmle Jr's first answer to that success was Frankenstein . The surprising (and lucrative) chemistry between Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland inspired Hal B. Wallis to put them in several romantic adventures, but none was a sequel to Captain Blood . Douglas Fairbanks Sr. did do one sequel to The Mark of Zorro after that film turned the course of his career, but that was just one of many swashbucklers he produced for himself. And so runs on the list of producers who felt the right way to build on a hit movie was to pursue comparable stories rather than stretch the same one out. The follow-ups weren't all gems; quite a few could be described as pale imitations. But even then, there was at least some pretense at offering a new story.

Not that there wasn't a temptation to do otherwise. Wallis considered sequels to hits like Captain Blood, and Warner Bros. even flirted with one for such a classic as Casablanca . Laemmle eventually would produce sequels to both Dracula and Frankenstein. Even Walt was briefly tempted to do a cartoon short that would serve as something of a coda to Snow White. And there's no point in pretending that sequels, remakes, and series are anything new in Hollywood. Tarzan (as played by Johnny Weissmuller) had a long-running series beginning in 1932, Universal eventually used the monsters from its most successful horror films to create a proto-cinematic universe, and Mickey Rooney cranked out Andy Hardy pictures for MGM over 21 years.

But the share of sequels has gone up over time, as has their prominence within the world of film. The Andy Hardy series wasn't nearly as pivotal to MGM's slate of pictures as Marvel has become to Disney. Except for the first two Frankenstein sequels, Universal's horror series faced dwindling budgets and uninspired recycling of plot elements. The general reputation of sequels and series was that of unremarkable B-pictures, the bottom rung on a double bill. They had fans, generated profits, and played their part in filling out a year's worth of content for theaters. But they weren't the life's blood of the studios. And audiences and filmmakers alike seemed to agree with Walt that the answer to a hit pig wasn't more of them.

Source: https://collider.com/why-walt-disney-didnt-like-sequels-explained/

0 Response to "Why Was Six Afraid of Seven Continuations"

Post a Comment